Latest Headlines

Of Manifestoes and Basic Needs

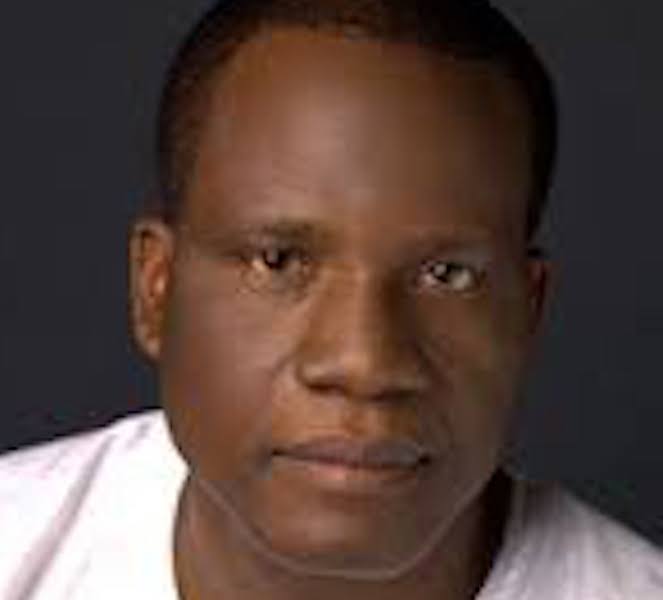

THE HORIZON BY KAYODE KOMOLAFE

KAYODE.KOMOLAFE@THISDAYLIVE.COM

0805 500 1974

In the build-up to the commencement of campaigns by political parties in the last quarter of 2022, the Independent Electoral Commission (INEC) stressed the imperative of issue-based campaigns. As the regulator of the electoral process, INEC was unambiguous in setting the ground rules for violence-free campaigns and healthy competition among political parties and their candidates.

For instance, at a meeting between INEC and security agencies on September 1 last year, INEC’s chairman, Professor Mahmood Yakubu said inter alia: “ As campaigns commence, we appeal to all political parties and candidates to focus on issue-based campaigns. This is the best way to complement our efforts to ensure transparent elections in which only the votes by citizens determine the winner.” The meeting was organised by the Centre for Democracy and Development 19 days to the publication of the final list of candidates for national elections by INEC. Beside INEC, other voices of reasons have been raised to urge politicians to focus on issues.

Unfortunately, few weeks to the elections the tone and tenor of campaigns are less than issued-based. The admonition by INEC has not been widely heeded by political parties and their candidates. Instead of robust debates of issues, political publicists ( otherwise legitimately promoting their candidates) as well as pundits and public intellectuals (expected to be non-partisan) have been trading insults and curses. Hardly is any vigorous debate of the issues of the election taking place at present. The differences in the positions of political parties and their candidates on the issues of the campaign are not prominently on display. Publicists and pundits (pretending to be doing political analysis) alike are rather busy demonising the candidates they are against while canonising the candidates for whom they are campaigning. Decorum has been thrown to the winds. And the reason for this abysmally low political culture should be obvious to those enamoured of reasoned approach to political campaigns: it is more intellectually tasking to discuss policy issues than to abuse opponents amidst a socio-economic crisis. By the way, media attention is not even paid to most of the candidates who are deemed “minor” against the rules of the game. That’s a topic for another day.

Meanwhile, the issues of the campaigns should be glaring for all to see. At a time when 133 million people have been officially pronounced as victims of multi-dimensional poverty, the issues of the campaign ought to be defined in the context of this grim reality of the nation.

Anti-poverty politics should not be optional if the object and subject of development are the people. For the overwhelming majority of the people who are expected to vote in the elections, the issues of the daily existence are those of basic needs. The mix of policies embodied in the party manifestoes should address these primary issues of existence. In other words, the 2023 politics should have the basic needs content.

The political pundits and publicists have focussed on religion, region, ethnicity, morality etc in distinguishing one candidate from the other. However, of a greater material relevance to the poor people are the issues of basic needs which are not hotly debated.

It’s not ethnicity, regionalism or religion that is the primary problem of a poor man in Nigeria. The real problem is a deadly combination of hunger, ignorance and disease. After all, as Karl Marx puts it in his famous statement of historical materialism, “ mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion etc.”

The basic needs approach to socio-economic development will require a fundamental confrontation with underdevelopment that’s plaguing the land. In fact, the socioeconomic problems are all symptoms of underdevelopment. The solution to this socio-economic malaise goes beyond the prevailing culture of governance by execution of random projects at all levels of government. With the basic needs approach, the end of the process would be the marked improvement in the quality of the lives of the people. This would, in turn, determine the means (in terms of the policy steps) to realise the ends. Central to the means is the power to make the policy choices. Every political economy is subject to limited resources. The deployment of the resources and what should be the trade-off are matters of political choice. In a people-centred policy arena, basic needs would not be the trade-offs in making policy choices. Take a sample. A state government internally generates meagre revenues. This poor state is faced with the choice between the provision of potable water to more communities and building an idle airport or other monuments of the governor’s tenure. The choice should be unmistakable: potable water is a basic need for the people. That is why the basic needs option in policy-making is also inherently a political economy approach. Here the interplay between political leadership and economic management comes prominently to the fore. By orientation, some politicians in power are disposed to the choice of making potable water available to all as a priority over building monuments that bear no immediate relevance to the basic needs of the people. There could be, of course, technical arguments for why the airport should be the priority – the need to open up the state for phantom investments in the absence of feeder roads. The raison d’etre of the political economy approach to issues of an election is that choices made in the path to development are ultimately political. The choices are not merely technical. If the poor people have the political power too, they would choose potable water (as an existential need) over an airport in which three flights may not be recorded in a week.

To tackle the underlying crisis of underdevelopment troubling Nigeria, the political economy approach is, therefore, indispensable. That should be a lesson from the last 36 years of Nigeria’s economic history for those who craft party manifestoes ought to consider. The way you approach the problems of a nation’s economy is a different from the way you sort out the woes of a corporate giant with the prescriptions of business school economics. The neo-liberal recipes for Nigeria’s economy are simply not working. This point is not conspicuous in the current campaigns .

Meanwhile, Chapter II of the 1999 Constitution lists these basic needs of the Nigerian people in terms of food security, social housing, basic education, primary healthcare, sanitation, social security, water, environment, mass transit etc. The chapter is entitled “Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policies.” Those who dismiss the constitution as a “useless” document never mention this chapter which bears greater material relevance to the lives of the people. In fact, if there is a genuine elite consensus on development, the manifestoes of every political party ought to be supremely informed by the Chapter II of the Constitution. By so doing, the basic needs of the people would receive a greater attention as part of the issues of elections. The allure of developed countries to which Nigerians emigrate is that basic needs are taken for granted in their destinations. Meanwhile, our neo-liberal experts would give you 1,001 technical economic reasons why those basic needs cannot be made available to the poor in Nigeria. These are the experts working on party manifestoes in every electoral season.

The good news, however, is that it is not too late for poltical parties and their candidates to heed the warning from INEC. The tone of the debate can still be changed in the remaining few weeks to the election with a focus on issues especially basic needs of the poor. To do so would be to enrich the quality of the process and invariably the outcome.