Latest Headlines

It’s All Politics

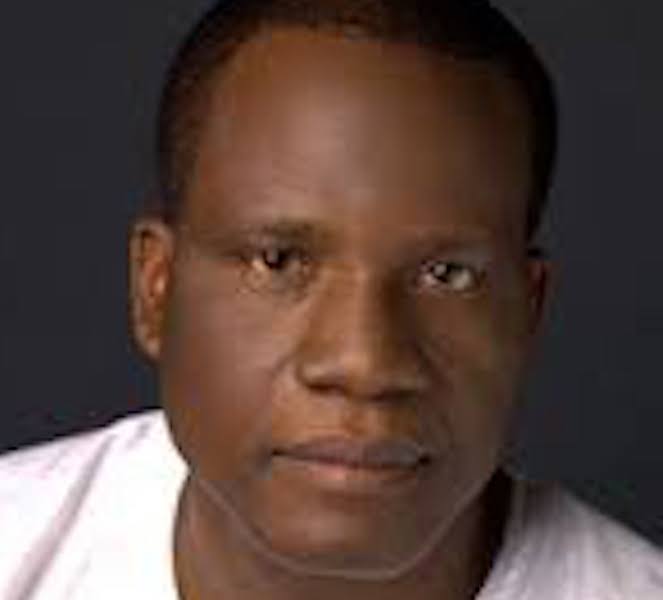

BY KAYODE KOMOLAFE

KAYODE.KOMOLAFE@THISDAYLIVE.COM

0805 500 1974

It is common to hear public intellectuals lament that re-reading essays written years ago would seem as if they are commenting on contemporary events. Perhaps, all you need to do to a column done a decade ago is changing the date and making a few updates and the piece would be like a current commentary.

The import of this is that the socio-economic and political problems that were the bases of commentaries in the past have essentially persisted to the present time. Seasons may change; but the issues hardly change.

In a way, this is a point made by a fellow columnist, Simon Kolawole, in his well-produced and dramatically entitled book, Fellow Nigerians, It’s All Politics: Perspectives on the Nigerian Project.

Now, as an aside, there is something ideologically problematic about referring to a country as a ”project.” Nigeria is not a project. It’s a neo-liberal categorisation to say that a country is a project, for implicit in the definition of a project is that you can even project into the time of its completion. Is it conceivable that any generation could ever complete the “project” of a nation? However, a reading of the essays would rather show Kolawole’s well informed perspectives on nation-building and development, and not a project. A century ago, almost a quarter of the world was under the British Empire. The empire stretched from Australia in the far east to the tropical nation of Jamaica in the west. Today, the United Kingdom is still grappling with challenges of nation-building and material issues of development as reflected in the energy crisis and cost- of -living strikes in the country. Recent news from Britain would normally be expected from a “third world” country. In effect, even Great Britain is not a project that’s completed. So much for the idea of a nation as a project!

Today’s column borrows its caption from the title of Kolawole’s 336-page book. Most of the essays embodied in the book have appeared on this page, although Kolawole expectedly did further editing on the essays in the book form. Kolawole usually addresses “Fellow Nigerians” as if he is making national broadcasts in his column! The themes explored in the pieces, written over a period of almost 20 years, are as far ranging as leadership, nation-building, political economy, development the psychology of politicians. In his highly insightful style and deliberately optimistic tone, the author provides historical contexts to issues.

As the electoral ferment engulfs the land, Kolawole’s book would make a refreshing reading as a reminder of what happened before in history and is still happening, albeit in different forms. Here is the kernel of Kolawole’s message to his fellow Nigerians : “The politics of purpose is often missing, giving way to prebendal politics and politics of pulling the wool over people’s eyes through a highly marketable sectional sentiments. Playing politics the right way- that is, for the greater good of the society- is critical to addressing the political, social and economic issues.”

In fact, many of those who are active in the public sphere in this season, but lacking a good knowledge of the historical contexts of things happening, will particularly find the book useful. This is because the build-up to this year’s elections is a proof that no two elections are the same despite some commonalities one election may share with the previous one. At least, one thing that the 2023 elections share with the previous ones is that “it’s all politics.” The sharp divergencies which are manifested in the campaigns are not primarily about policies. Political publicists are more comfortable attacking personalities rather than debate policies. Incendiary statements are issued daily. But the statements are not about issues. Criticisms have degenerated into hatred. Pronouncements on the immediate future of Nigeria are made in absolute terms as if February 25 will be the end of history.

Well, this reporter can also volunteer his own prediction too: there will be life after the elections despite the extreme positions of the publicists.

Meanwhile, arguments are often mechanically presented in binary terms of hell and paradise. It does seem that for some publicists Nigeria will become a paradise if their candidate wins while the nation would turn into hell if the candidate they oppose is victorious. Yet, the realistic projection is that whoever wins, by this time in 2027, when another election fever would be on, Nigeria will neither be a paradise nor a hell. There are, of course, a lot of possibilities between the two extremes being falsely presented by some propagandists as the only options. In a probably idealised way of putting things, the electorate would make informed choices hoping that if their preferred candidate wins the quality of lives of the people will be relatively better in four years from now.

The February 25 election will be the 10th presidential election since 1979 when Nigeria adopted the American-style presidential system while dumping the British-like parliamentary system. Of the nine presidential elections the nation has had, six have taken place in this Fourth Republic.

In the previous presidential elections phrases such as “make or mar,” “do or die” and “ the coming of Armageddon ” were used to describe what was expected in the course of preparations for the respective elections. Again, a lot of fears have permeated through the political landscape in this electoral season. Scaremongering has become the pastime of some mischief makers. These fears emanate from the intrigues of politicians. As Kolawole argues eloquently in the book, “if politicians devote just 10% of their intrigues to making Nigeria better, I bet Dubai would be like a ghetto.” To put things in class terms, if the common purpose of politicians is to wage an anti-poverty war, Nigeria would be like 40 Norways put in a geo-political space, given the low rate of poverty in the Scandinavian country. Gross inequality is also a socio-economic problem of Nigeria; it constitutes an obstacle on the road to poverty reduction. But politicians don’t talk about it in Nigeria for obvious class reasons.

The challenge of the moment before the nation, therefore, is to forge a consensus on the point that it should not be all politics when talking of development and nation-building.

GUEST COLUMNIST

SAM AMADI

Democracy and the Judiciary

Chukwudifu Oputa, a reputed Justice of the Nigerian Supreme Court, once noted that the Supreme Court is final not because it is infallible, but infallible because it is final. Another reputed justice of the Supreme Court, this time of the United States, Learned Hand, pointed out that it would be irksome to be ruled by a ‘bevy of Platonic Guardian’, and have them determine public affairs rather than by my vote. These two statements come into view as we ponder the impact of two controversial decisions of the Supreme Court in the runup to the 2023 presidential election in a couple of weeks. These decisions, plus the Election Tribunal’s judgment on the Ondo State Governorship Election dispute, cast the 2033 election into the tempest of uncertainty. Will the courts choose the winners against the votes of the electorates, or will the courts affirm the decision of voters?

These two statements set out the crisis of the involvement of the court in picking who gest to govern the rest of us through democratic elections. Judicial supremacy seems to have become an established convention of representative democracy especially of the constitutional democracy types. The justification for the involvement of courts in the struggle for political power is inherently linked to the idea of democracy itself. That is, to protect the minority from the dangers of majoritatisn politics. Democracy is both an ideal and a set of institutional arrangement. As an idea, democracy represents the notion of self-determination. Each of us is unique in our autonomy. Democracy proclaims equality of status. Thus, everyone should be able to determine the rules and norms that will shape their activities, and not to herded into submission by majority.

The idea of democracy as self-determination is feasible in a city state where everyone can participate in democratic deliberations that lead to law-making. With complexities of space and subject matter of public policymaking, the need for representation becomes overwhelming. Today, for all practical purposes, democracy now means representative democracy, which has further mutated into electoral democracy. Electoral democracy is now translated into institutional arrangements, or what the famous political scientist, Robert Dahl, calls ‘institutions and practices’. The three most important and defining features, practices and institutions of electoral democracy, according to Larry Diamond and other scholars, are extensive competitive, political participation, and civil and political liberties. Electoral democracy requires that there is competition for the right to govern. Many sceptics of electoral democracy argue that the competition of electoral democracy is elitist and therefore not equalitarian. But without extensive competition, electoral democracy is even worse than sham. This competition requires widespread political participation of the citizens. The process of democratic elections must be characterized by civil and political rights.

If these minimum requirements of electoral democracy are missing, a political order is no longer democratic, despite other institutional grounding of the exercise of political power. this may be the reason the University of Gothenburg’s Verities of Democracy Institute in its 2022 report describes Nigeria as an ‘electoral autocracy’. Their point is that Nigerian elections lack the desired level of competition, and its process are deficient of political and civil liberty necessary to confer the stamp of democracy on them. The fact that we hold periodic elections, the fact that in 2015 we had an incumbent government defeated in elections and power was peacefully transferred do not mean we have attained even the status of .hybrid democracy’ as the Freedom House Report classified us in 2021.

The 2022 Electoral Acts tries to cure some of these deficiencies that turns Nigeria’s efforts at democracy into ‘electoral autocracy’ by democratizing the process of election through enhancing political participation, engendering extensive competition and entrenching respect for civil and political rights of the citizens. The primary problem with Nigeria’s electoral system is the lack of internal democracy in the political parties. If as Robert Dahl and others have argued, the beauty of democracy is that it allows competition and public participation, then the level of democratic participation in the political parties is very important.

It is this feature of democracy that has lacked for long. Nigerian political parties have been run mostly as private franchise. It is a form of autocracy. The few who gain control of the machinery of power in the parties have used that power to impose candidates on the electorates thereby defeating the requirement of extensive political participation. The Supreme Court gave legitimacy to this privative practice by the obtuse concept of ‘internal affairs’ of the party which undermines competition and denies party member of political participation, which is the most important aspect of democratic election of candidates. This concept which made its unholy appearance in a decision by the revered Justice Obaseki in the 1980s have been cast into deserved oblivion, only to be resurrected by the Supreme Court in two recent cases. In the cases of Governor Akpabio and the Senate President, Senator Lawan, the Supreme Court undermined internal party democracy and legitimized any decision the party leader makes in the name of the party because it is the party that chooses candidates, notwithstanding that the electoral law has stipulated how candidates should emerge.

The implication of washing its hand from the need to protect the rights of the members of the party is that the Supreme Court has wittingly or unwittingly rewritten the cardinal rules of Nigerian democracy and helped to entrench it as an ‘electoral autocracy’. The new electoral law understands the pathology of Nigerian politics and enshrined a regulated process that ensures that party members are able to determine who they present to the electorates in a democratic manner. Sections 84 and 85 are elaborate constraints to address the freewheeling of party bureaucrats. To strengthen this regulatory process, the Act requires parties to submit the membership lists to the regulator of election for verification before holding any democratic congress. The regulator is also mandated to attend such congress or primary to confirm the results.

Previous electoral regimes did not have such express provisions which deceived the Supreme Court to support the usurpation of the rights of party members by party leaders. The purpose of the change is to enable the election regulator to have a step-in right to reverse such usurpation and to help the court to reassert the rights of party members to choose their candidates. But the Supreme Court in one moment of illogic has incinerated the evolution of political practices that have culminated in a policy redress of a perceived malady. The Supreme Court is final but fallible. The faulty audacity of this ‘Platonic Guardians’ would irk Learned Hand himself.

In pursuit of the principle of ‘internal affairs of the party, the Supreme Court has put a man who did not contest elective primary as the candidate for the Senate. This man is the third highest ranking political officeholder in Nigeria with all the suggestions that he may have ‘wangled’ his way onto the electoral slate, notwithstanding the ‘pretences’ of the electoral law. As Justice Wendel Holmes would say, law is what the court say it is and nothing more. The Supreme Court has imposed a candidate who did not contest primary election. There may be many technical reasons to justice this imposition. But the truth is that it detracts from the intention of the electoral law and is another evidence of the poor results of judicialization of politics.

In the runup to the 2007 general election, I argued in an opinion piece that it was the judges who will select the winners. I made the point after observing how party leaders brazenly hijacked their party leadership structures, distorted elective primaries, and imposed their cronies as candidates of the parties. They did not just impose candidates at will, but also changed them at will. I concluded that obstruction of due process would incense the judges to hit back at party leadership and impose candidates. The prediction turned out to be right. From Senator Ifeanyi Ararume to Rotimi Amaechi, the Supreme Court brazenly overruled the party leaders. Sadly, they also overruled the electorates.

In the Ararume case, the Supreme Court nullified the nomination of the Charles Ugwu as the PDP governorship candidate for Imo State and declared Senator Ararume as the lawful candidate of the party. The PDP hit back by campaigning to its supporters to support the candidate of another party and not its own Supreme Court-imposed candidate. The PDP had its way. Its candidate was defeated. In the Rotimi Amaechi case, the Supreme Court learnt the lesson. It didn’t only declare that Amaechi ought to be the candidate, but it also installed him Governor even without Amaechi being a candidate in the elections. After being castigated for this unprecedented judicial recklessness, the Supreme Court asked that its decision should no longer be considered as good law.

The trend of judicialisation of politics and elections in Nigeria has not abated. The new electoral law has tried to insert the electoral management body, not the courts, at the heart of elections. But the courts continue to be more determinative than even the electorates. The judicialisation of electoral politics raises serious concerns for democracy and governance.

First, the more courts decide outcomes of electoral contests, they may make politicians focus on the management of judicial outcomes rather than political engagement in their quest for political power. This is dangerous for democracy. It weakens the legitimacy of judicial review as a non-partisan, counter-majoritarian framework to manage politics when it draws away from basic rights, and not to override politics when it does not threaten fundamental rights of minority groups. The idea of representative democracy is that the people, ordinary people, should rule themselves through those they choose, not those that enlightened elites prefer. It is right as Justice Learned Hand said, that one does not want to be ruled by a ‘Platonian Guardians’ but by elected representatives. When judges usurp the right to elect representatives, they empty electoral democracy of its meaning.

Furthermore, as judges continue to insert themselves into electoral management through unprincipled determination of winners, they corrupt themselves. It is noteworthy that corruption surveys show that the judiciary is competing with police for the top spot on the corruption perception index. The increasing corruption in the judiciary may bear relation to its intermingling with politician on electoral matters. The temptation from desperate politicians wishing for favourable decision from the court is one that many Nigerian judges are not ethically and intellectually fitted to overcome. It is better to get them farther from the politicians than closer if we want to control judicial corruption.

It is a difficult task to walk the fine lines between a judicial review that is compatible with judicial deference to politics and one that crowds out the will of the people and the political branch in choosing representatives. I think one rule of thumb for not crossing the red line is to develop a coherent and intelligent theory of electoral democracy and build a deferential election jurisprudence from it. Democracy requires that the people govern themselves. The spatial complexities of a modern state means that citizens cannot gather at the Agora to make law and take turns to execute and adjudicate on the law. They choose amongst themselves a few to do so on their behalf.

Every democratic order should always aim at upholding the right of the people to explicitly make the decision on who represents them. The court’s role is ancillary: it reinstates this power where usurped by bureaucracy and correct the exercise of majority power that damns the minority. The court should only intervene to determine winners and losers of an electoral contest when it must restore the choice the people have made. The court should never assert its choice in whatever guise against the choice of the people.

The requirement of judicial deference to the people and the political branch in matters of choice of representatives of the people does not mean the nonsense about the internal affairs of the party that the Nigerian Supreme Court has wrongly elevated to a doctrine of law. Where party leaders violate the electoral law and present candidates for election different from candidates that members of the party had proposed in democratic primaries, it is part of an enlightened jurisprudence of electoral democracy for the court to step in and reverse the fraud against the people. The court should not allow party bureaucrats to take over the right of party members to select candidate in the name of deference to internal management of the party.

The solution to judicialization of politics is for the political regulatory process to work. First, we should have politicians who are smart enough to regulate themselves through a more inclusive and rule-based political behaviours. Then we need to have an election management body that is not missing in action, one that understands and effectively utilizes regulatory tools to achieve competitions, participations and civil and political rights in the electoral process. When these two pillars are in place, the third pillar, the judicial regulation can be organized as a light-touch review of regulatory action that ends with a remand to the party or the regulator to do its job better, and not an usurpation of political decision by the non-political branch ends in Judges choosing winners and losers themselves.