Latest Headlines

The Logic of Solidarity

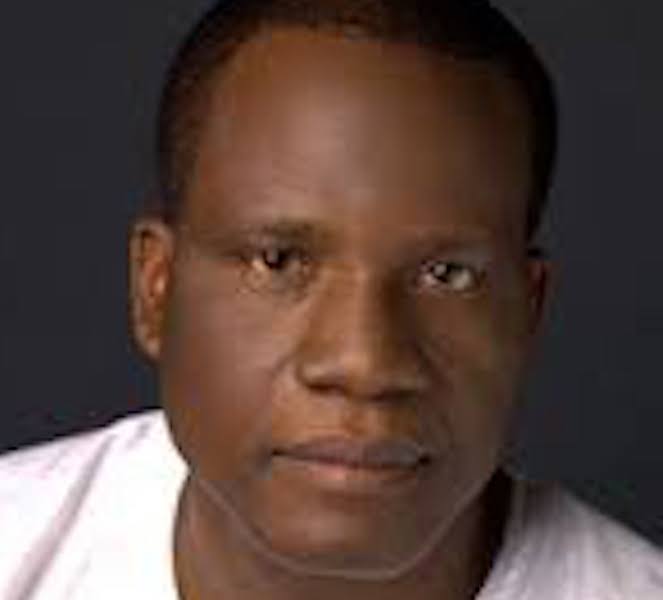

Kayode Komolafe

kayode.komolafe@thisdaylive.com

0805 500 1974

The lingering question of how mankind could strike a balance between competition and cooperation is implicit in the focus of the 78th United Nations General Assembly which opened yesterday in New York, United States.

Nations have to find an urgent answer to this central question of existence as they grapple with the basic issues in their economies, polities and societies

This year’s meeting of world leaders has the following theme: “Rebuilding Trust and Reigniting Global Solidarity: Accelerating Action on the 2030 Agenda and its Sustainable Development Goals towards Peace, Prosperity, Progress and Sustainability for All.”

It is fitting that global attention is on the idea of cooperation in the face of problems that confront humanity as a collective. Such problems cannot be solved by socially blind competition. The solutions would rather be enhanced by solidarity.

President Bola Tinubu spoke appropriately on the theme and the sub-themes from the Nigerian perspective touching on sustainable development, climate change, global cooperation inequality and global humanitarian crises.

In the light of the urgency demanded in responding to these issues, the United Nations (UN) is understandably suggesting the acceleration of action on the 2030 Agenda on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set in 2015. However, a cloud of pessimism would hover in the background of the sessions for obvious reasons: half way through the 15-year period proposed for the realisation of the goals none has been achieved. And the future prospects are far from being bright. Indeed, only in July, the UN published a status report indicating that the SDGs “are in peril” what with the soul-depressing fact that barely 12% of the targets are on track. The grim report also indicates that about half of the goals have suffered varying degrees of setbacks.

Just imagine the goals: “No Poverty; Zero Hunger; Good Health and Well-Being; Quality Education; Gender Equality; Clean Water and Sanitation; Affordable and Clean Energy; Decent Work and Economic Growth; Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure; Reduced Inequalities; Sustainable Cities and Communities; Responsible Consumption and Production; Climate Action; Life Below Water; Life on Land; Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions; and Partnerships for the Goals.”

The pessimism about the realisation of the goals in many countries is said to be shared by the government, private sector and the civil society. In fact, some experts are already wondering if the SDGs can ever be saved given the obvious lack of capacity of many countries to reach the goal.

The practical implication of this lack of meaningful progress in the realisation of the goals is manifest. Globally, about a quarter of young people are out of school or work, the earth itself is getting hotter by the day and the sea is becoming more acidic. About 1.1 human beings are still victims of acute multi-dimensional poverty in 110 countries.

Solidarity among nations is essential for global issues to be resolved for the sake of human progress. Failure to tackle some of these problems in the spirit of cooperation may put the future of mankind at risk. Unbridled competition among the strong and the weak nations may not be helpful in the present circumstance of humanity. Individualism and greed will not advance the cause of mankind. The public purpose should be the pull for action. This reality should inform the underlying philosophy of social and economic policies

This point could be illustrated by examining the way the world is tackling some of these big issues – climate change, inequality, pandemics and migration.

Perhaps, the coronavirus pandemic is the most chilling reminder in recent years of the primacy of our common humanity. COVID- 19, the disease caused by the virus has claimed about 6.9 million lives. Cooperation rather than competition suddenly became the dominant trend in the responses by different countries. The global reach of the biological disaster caused by the pathogen has proved the World Health Organisation (WHO) right: “No one is safe from COVID-19 until everyone is safe.” The interconnectedness of social and economic activities of peoples across nations was laid bare by COVID-19. The solution for the problem was not hinged on competition. With the coordination done by the WHO, solidarity was the watchword at the peak of the public health crisis. The outbreak of the disease was in China. Within months countries in the American continent already had their public health systems overwhelmed by the disease. Global supply chains were severely disrupted. The public health crisis triggered a socio-economic crisis. Everywhere in the world people looked up to responsible governments to have a grip of things in combatting the spread of the virus and the disease caused by it. The role of an effective state became central in the scheme of things. The quality of the public health system of each country was put to a monumental test. The principle of solidarity was more prevalent than that of the market in the distribution of the vaccines developed to combat the disease. A take-away from COVID-19 is that healthcare delivery is a public good. Investment in it should be informed by that logic.

Climate change is another phenomenon that should temper humanity’s instinct for mindless competition. Each sovereign nation or economic bloc makes increased growth rate a goal of its political economy. Economic advisers urge governments to make their national economies more competitive. Some nations have even been reduced to “emerging markets” that should be made “competitive.” Policies are implemented in the pursuit of this legitimate economic and social objectives within their national or regional boundaries. But the ecological consequences of these activities transcend boundaries. With the melting of sea ice and global warming, parts of the world are increasingly becoming inhabitable as result of floods, fires and atmospheric pollution. The climate change has shown that for centuries world capitalists hardly gave a thought to the condition of the earth as they pursued profits. That has been the mega trend since the industrial revolution.

The approach towards saving the common habitat can only be that of cooperation and not competition. After all, regardless of the legality of national boundaries the habitat of humanity is the earth.

In response to existential risk of climate change world leaders came up with the “Paris Agreement” on how to address this common problem of humanity. The agreement was drawn up in December 2015 at the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Paris, France. It came into force a year later . Essentially, it is a legally binding international treaty adopted by 196 parties on the way to tackle climate change. The major goal of the treaty is to keep “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degrees centigrade above the pre-industrial levels” while striving to “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees centigrade above the pre-industrial levels.” Social and economic transformation would be required to achieve the purpose of the agreement. Eventually, it would lead to a global transition to clean energy. Again, the underpinning principle is that of cooperation and solidarity and not competition. It cannot be competition any more because the excessive competition for economic growth and years of mindless consumerism are partly responsible for the present state of global ecology. Rich nations are expected to demonstrate solidarity with poor ones in environmental distress. Developed countries made the pledge to provide the finance, technology and capacity building for the poor countries to join the train moving towards a significant reduction in carbon emission. Unfortunately, a sense of urgency is lacking on the part of the rich countries. They are yet to demonstrate in action that the treaty is indeed binding on them as their commitments are hardly fulfilled.

Inequality is a social plaque that exists among nations and within nations. A majority of the human population has been excluded from partaking in the benefits of globalisation. Individualism and greed have widened the social gulf within nations. In 1944, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), one the oldest UN agencies, declared in Philadelphia, United States that “poverty anywhere constitutes a threat to prosperity anywhere.” The truism of that statement today is indisputable. The social convulsions are experienced in poor and rich countries alike are proofs of the veracity of that declaration. So it is apposite for the UN to make poverty reduction a top most goal on its agenda. The migrant crisis afflicting parts of Europe is also a reminder that tackling global poverty requires more of cooperation than competition. As the proceedings of the 78th UN General Assembly continue, more than 7,000 migrants are having an immigration battle with officials in the Lampedusa Island in southern Italy. The migrant crisis has again demonstrated the fact the mass poverty and widening inequality are common problems of humanity. The migrants from the poor countries of the south are asserting their common humanity to the face of the people in the rich countries of the north by forcing their way through the borders in pursuit of better life. It is clear that the migrants have no respect for the legality of the borders. That is their own form of globalisation. This has become a moral crisis for European countries. After all, centuries ago there were earlier forms of globalisation in which slave traders, pirates and colonial agents backed by European monarchies and governments rampaged other parts of the world taking human beings and wealth to their countries. For instance, in those epochs there were no borders and no one issued the Europeans any visa to come to Africa.

Solidarity is, therefore proposed as an element in the process of finding definitive solutions to these common problems of humanity.

Reflecting on these big issues, Oxford University philosopher, Toby Ord, says that given the grave nature of the risk humanity faces the first thing to do is to take urgent action that could make the world reach “a place of safety” so as to allow time for further reflection about the future. In his book entitled “The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity,” Ord makes the following proposition: “If we steer humanity to a place of safety, we will have time to think. Time to ensure that our choices are wisely made; that we will do the very best we can with our piece of the cosmos. We rarely reflect on what that might be. On what we might achieve should humanity’s entire will be focused on gaining it, freed from material scarcity and internal conflict. Moral philosophy has been focused on the more pressing issues of treating each other decently in a world of scarce resources. But there may come, time, not too far away, when we mostly have our house in order and can look in earnest at where we might go from here. Where we might address this vast question about our ultimate values.

This is the Long Reflection.”

As the world leaders are making their great speeches in New York, it is important for the rest of us to focus our reflection on these mega trends.