Latest Headlines

The Thoughts Behind Policy

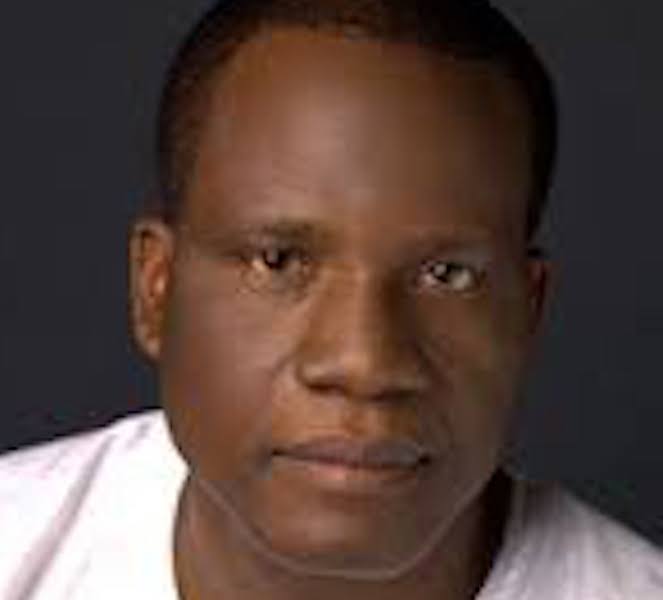

Kayode Komolafe

For those seeking the underlying logic to the politics of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) minister, Nyesom Wike, and his disposition to policy, the yesterday edition of his signature media chats might provide some clues.

As an aside, it should be remarked that the Wike Media Chat has evolved as a peculiar form of projects’ advertisement which has its provenance in the politician’s days as the governor of Rivers state. It’s done in the Wike style!

A member of the yesterday panel of interviewers, Chamberlain Usoh, of CHANNELS Television asked Wike a question on the availability and affordability of healthcare delivery in the FCT. The interviewer pointed to the problem of few bed spaces and the lack of health insurance for the poor among other issues.

Here is Chief Wike’s reply to the question of making healthcare available to the poor: “…When you say affordable (it shows) that we live a life where things (are) free for (everybody). We are not in a socialist regime. We are not…” Wike also dismissed the idea of the urgency of increasing bed spaces saying that what mattered was bringing in standard equipment to the hospital. Remarkably, the minister used words such as “plan,” “conception” “standards” “costs” etc. in the course of the conversation. These are, of course, familiar words often used in the process of policy making and implementation.

Meanwhile, Wike, who likes to be addressed as “Mr. Project,” is expected to implement the N1.1 trillion budget for the development of FCT. And to imagine that universal healthcare coverage would not be a priority in the implementation of a N1.1 trillion budget!

Now, that is not the path of development.

As a matter of fact, Wike earned the sobriquet of “Mr. Project” in his days as Rivers state governor when for almost a year he staged spectacles to “commission projects.”

The minister also spoke about some infrastructural projects in the course of the yesterday media chat. Wike’s response to the question of his policy in the health sector of the FCT is reminiscent of what a former governor told this reporter some years ago : he said what happened in the states including his own was “governance by projects.”

Now, there is something fundamentally problematic about the concept of development on the part of a minister who doesn’t prioritise the affordability of healthcare delivery to the poor in a country in which it is estimated that 63% live in multi-dimensional poverty. Healthcare is a major pillar of human development. Without the micro impact of human development especially on the majority poor, all the multi-trillion contracts for infrastructure will achieve little or nothing in advancing human progress in the society.

At least on record, Wike is a member of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), an organisation which cannot be accused of being socio-democratic in ideological preferences. However, Wike is today a minister in a government of the All Progressives Congress (APC). By definition, a government of APC at any level should prefer progressive options in policy-making. Progressive politics in Nigeria today is nothing if it is not an anti-poverty politics. For poverty and inequality constitute the bedrock of the problem of the Nigerian society at present. Experts of various hues have drawn an organic link between poverty and insecurity. In other words, insecurity cannot be ultimately tackled without eradicating poverty and reducing gross inequality. So it is never progressive for any politician to say that making a case for affordable healthcare is akin to expecting “to have everything free.” To dismiss universal healthcare coverage, a central question of human development, is far from being progressive in the present Nigerian condition. Contrary to Wike’s policy proposition, universal healthcare is not necessarily an agenda of a “socialist regime.” Universal healthcare is available in many capitalist countries in different forms. For instance, despite its imperfections the British National Health Service (NHS), a heritage of the welfare state, is cherished as a national institution and defended by Britons across the political and ideological spectra. Yet, Britain is not a socialist state. Here in Nigeria, the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) Act (2022) and the FCT Health Insurance Scheme established with the instrument of the FHIS Act of 2020 were enacted for the ultimate purpose making healthcare affordable to all. In fact, the goal of FHIS is to reengineer the health care funding mechanism to achieve universal health coverage in the FCT. And these are no laws made by a “socialist regime”!

For Wike, the practical politician, ideological debates about policies may be a luxury. All the “action man” would be concerned with is to award contracts for infrastructural projects and supervise their execution for delivery according to schedule.

In the process, little attention is paid to the organising principle of the execution of these projects within a broad concept of development. Perhaps, unknown to the minister, the implication of his laissez faire attitude to universal healthcare coverage is that market forces should determine the access to quality healthcare.

Today’s column is making the foregoing reference to only an aspect of the Wike media chat just to illustrate the point that there are indeed thoughts behind policy-making. These thoughts emanate from the worldviews of the policymakers. Wike is not alone in not prioritising the social sector – heath, education, social housing, mass transit etc. in policy-making.

One of the consequences of this orientation of officialdom is the socio-economic injustice that has ravaged the land for decades.

Some Nigerian politicians and pundits alike glibly proclaim the end of ideology. Yet ideology is alive and shaping policies around the world. To be sure, those making choices for the society in the policy arena may not be fully conscious of their ideological options, much less articulate the ideology. Some of those who are conscious of their ideological choices deny their ideologies because their choices are simply indefensible. Policy dispositions that could worsen poverty are no more defended even by right-wing ideologues. Unlike their socially ruinous economic prescriptions of the 1980s, even the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the chief enforcers of global capitalism, have since adopted anti-poverty tone in their policy prescriptions for the poor countries of the world.

Doubtless, policy-making in Nigeria cannot not be said to be an exercise in a vacuum of ideas. Think tanks and other non-governmental organisations abound with harvest of ideas. For instance, for 31 years now the Nigerian Economic Summit Group (NESG) has provided a forum for dialogue among private sector players and public sector officials on the shape and future of the Nigerian economy. But the question persists: to what extent have the ideas generated on the platform of NESG influenced policies of successive administrations? The same question could be posed in respect of the Ibadan-based Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research (NISER), which is publicly funded for the production of ideas and information to illuminate the process of policy-making. The question of the impact of these institutions and many others on policy is certainly not a rhetorical one. The question has to be definitely answered to make progress.

Talking about the ideological influences on policymakers, Nigeria is yet to fully develop the culture of a well-defined ideological direction pushed by men of ideas. In history, leaders had thinkers widely acknowledged to have influenced their policy directions. The ideas in favour government-intervention proposed by the eminent economist, John Maynard Keynes, had a lot of influence on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal during the Great Depression. If Roosevelt was influenced by Keynes, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was ideologically inspired in the opposite direction by the Austrian-born British economist Friedrich von Hayek, a free-market economist who believed that government control of the economy was akin to “totalitarianism.” The monetarist economist and Nobelist Milton Friedman was the oracle of the Chilean economic experiment under the maximum ruler, President Augusto Pinochet. The foregoing are, of course, liberal and conservative examples. Things are more explicit on the Left. For example, despite the cynical western comments about China becoming a capitalist country, the leadership of the country is still guided by the “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era “

In fact, Keynes, regarded in liberal circles as the greatest economist of the 20th Century put the matter of ideas behind policy like this: “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

It is, therefore, noteworthy that the current economic managers of Nigeria are giving some thoughts to planning as a signpost to policy-making. The other day, those in charge of fiscal and monetary policies appeared before the Senate to brief the lawmakers on the economy. One of them, the minster of budget and economic planning, Senator Abubakar Atiku Bagudu, instructively drew the nation’s attention to the organising principle of economic management in Nigeria. He referred his audience to the national economic objectives enshrined in the Section 16 (2a) in the Chapter II of the 1999 Constitution, According to the provision, the state shall among other things ensure the “the promotion of a planned and balanced economic development.”

So planning is fundamental to economic development of Nigeria.

From the East to the West on the globe governments plan economies to meet their respective national objectives. China couldn’t have achieved its economic progress without planning. This is one riddle that is hardly understood by even the experts in the West when they assess the development of China. The economic managers of China employ the market to serve their defined purpose. They do not surrender their economy to market forces in some sectors. China couldn’t have implemented the most successful poverty reduction programme in economic history by blindly surrendering its social sector and other crucial areas of its economy to market forces. It would be more difficult for a poor country to lift its people out of poverty significantly when universal healthcare coverage and basic education are reduced to commodities.

It goes against the grain of poverty eradication to throw sectors such as health and education to market forces. Yes, market forces are applied in capitalist societies. But the market has its limit especially in a poverty-ridden society: there are sectors in which market forces should not even be contemplated. Instead, of the reckless embrace of the market, policymakers should strive to plan for the common good.

Nigeria should plan its way out of poverty. And that is not a job for market forces.

There are even liberal voices offering a word caution on the matter of jettisoning planning for the market. For example, a South Korean economist, Ha-Joon Chang admonishes in his famous book, “23 Things They Don’t Tell You About Capitalism,” as follows: “The question … is not whether to plan or not. It is what appropriate levels and forms of planning are for different activities. The prejudice against planning, while understandable given the failures of communist central planning, makes us misunderstand the true nature of the modern economy in which government and market relationships are all vital and interact in a complex way. Without markets we end up with inefficiencies of the Soviet system. However, thinking that that we can live by the market alone is like believing that we can live by eating only salt, because salt is vital for our survival.” Chang is by no means a socialist. He actually believes in the superiority of the capitalist economy. But he is rational enough to deploy his scholarship to warn against the excesses of the system.

Those who have the responsibility of making economic policies should be suggestible enough to ponder this point.